UK

The UK has an incredible range of native wildlife and habitats, from red squirrels and water voles to ancient woodlands and vibrant wildflower meadows. Looking after this biodiversity isn’t just about protecting species—it’s about bringing nature back into our everyday lives. By restoring habitats, carefully reintroducing lost species, and involving local communities in conservation, we’re working towards a future where wildlife thrives right alongside people.

Here in the UK, we work to conserve and restore our estate, as well as working with regional partners to drive conservation at the landscape scale. Our approach to forestry, which involves continuous cover forestry, our historic parkland, and the management of our estate, has created space for a wide range of native species. From the cheddar pink, an endemic to Cheddar Gorge, to the fourteen bat species that use the estate's historic houses, ancient trees and caves to roost, these show our management of our land is great for biodiversity. We have also reintroduced water voles alongside the recolonisation of the estate by beavers, pine marten, goshawks and wild boar. This thriving ecosystem is carefully managed to ensure we can maintain a balance, whilst making space for other species to return.

Water Vole Project

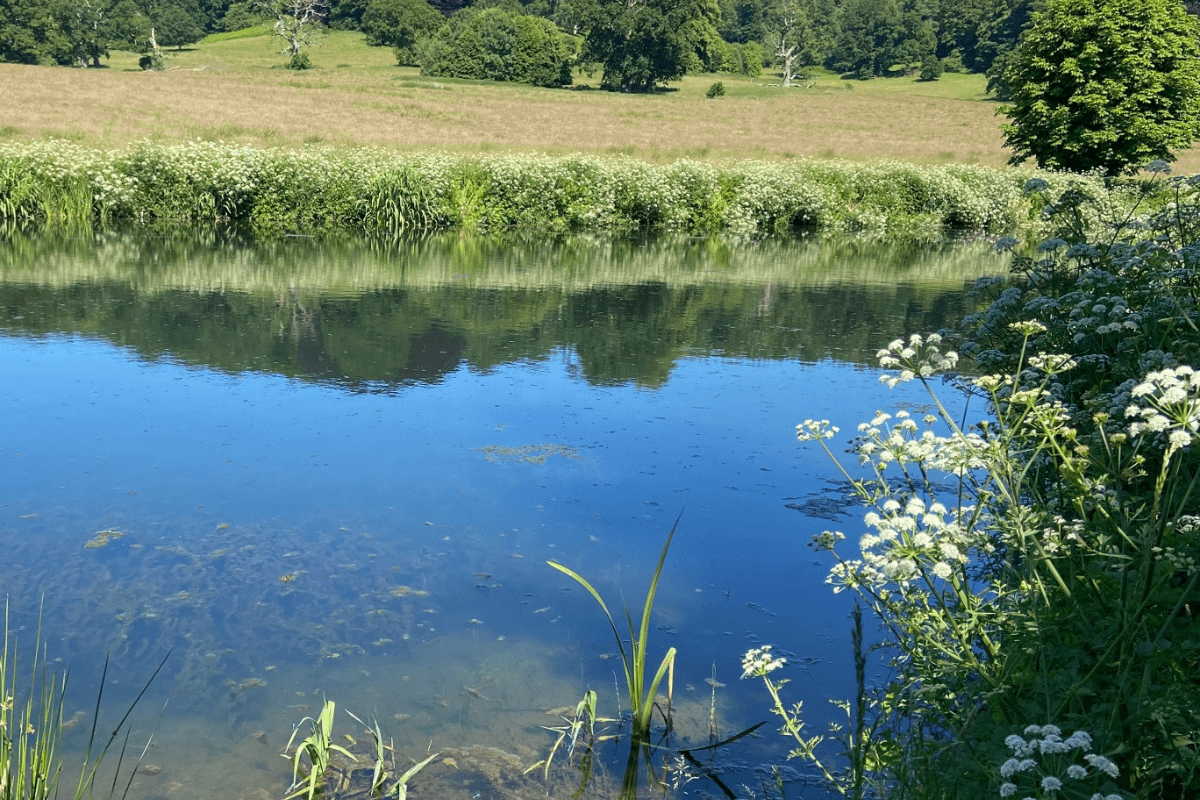

The famous ‘Ratty’ from the novel The Wind in the Willows is in fact a water vole (Arvicola amphibius). Living in waterways, nibbling on grasses, burrowing into river banks these wonderful animals are now unfortunately very rare. Only by recreating and maintaining their habitat, and through protecting them from the invasive American mink, can we help the water vole survive.

Longleat is very proud to be working with our conservation partners on a reintroduction programme across the Estate. In June 2022, the first reintroduction of 50 water voles took place. Ten of the water voles were immediately released back into the wild, while the remaining 20 pairs were temporarily placed into holding pens to enable bonding time before being set free. All of them are micro-chipped and future recapture surveys will identify wild bred progeny and study dispersal rates.

A number of the animals released at Longleat were translocated from a building site under licence from Natural England, while others are part of a captive breeding programme for the species. Longleat has been working alongside ecologists from the Derek Gow Wildlife Consultancy on the project. Supervised and legislated by Natural England, this project required a suitable environment for animals to be moved safely. Following an onsite ecology survey and arrangements on security, pest control and habitat protection, it was agreed Longleat offered an ideal location.

Fortunately, the Longleat Estate is a diverse habitat which will help these animals to prosper and become part of the local landscape once more. Further releases are planned to try and ensure the strongest and most genetically viable population possible.

Cheddar Gorge

Bats at Cheddar

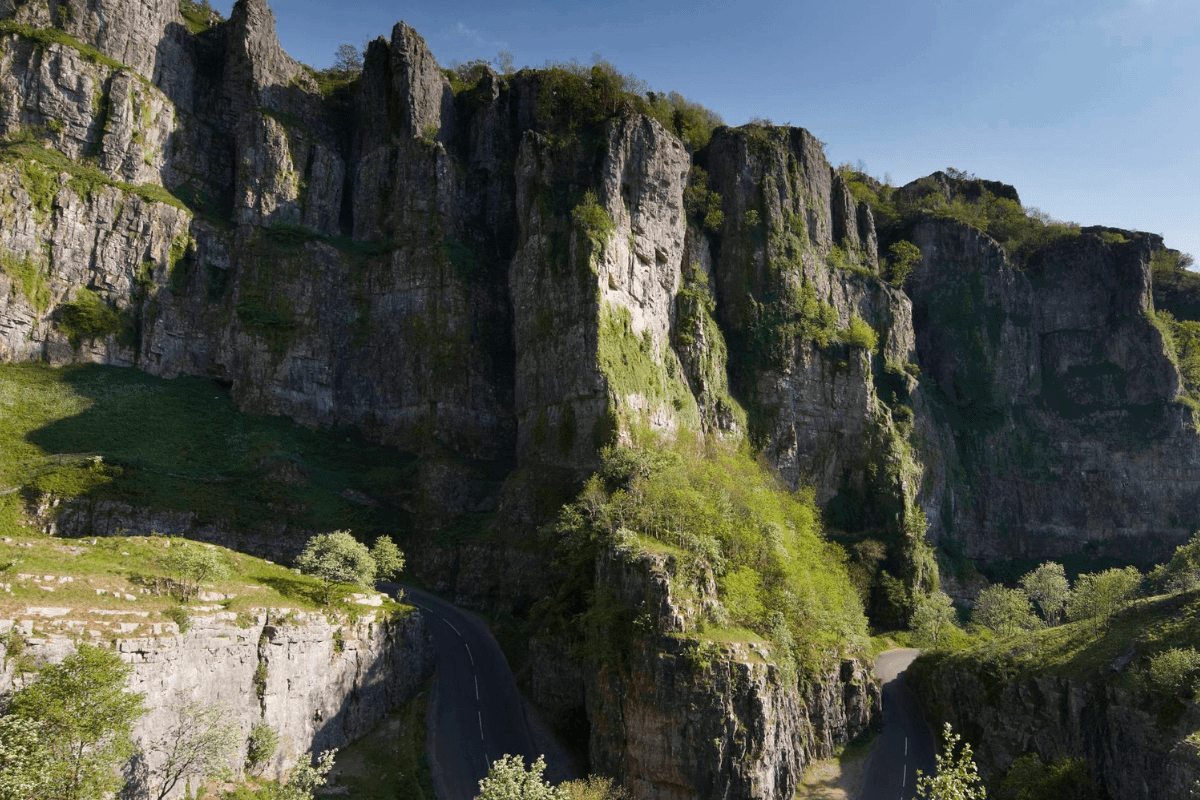

"Cheddar Gorge is more than just a spectacular landscape—it’s one of the most important sites in the UK for horseshoe bats. These remarkable animals depend on the caves here for winter hibernation, with some even staying year-round to raise their young. Our ongoing monitoring shows just how vital this place is for both greater (Rhinolophus ferrumequinum) and lesser horseshoe (Rhinolophus hipposideros) bats, two of the country’s rarest species.

The caves at Cheddar offer precisely the right conditions: cool, stable temperatures, high humidity, and the quiet, undisturbed spaces bats need to survive the winter. Greater horseshoe bats are especially dependent on Gough’s Old Cave, which supports one of the largest known breeding colonies in the country, representing around 3% of the entire UK population. A small heater, installed decades ago, continues to support the colony by maintaining warm temperatures for maternity roosting.

But it’s not just the caves that matter. The surrounding landscape—old woodland, species-rich grassland and low-intensity farmland—forms a rich mosaic of foraging habitat. These bats travel widely across the area each night in search of beetles, moths and other invertebrates. That’s why careful land management matters as much as what happens underground.

Grazing plays a key role in maintaining that rich habitat. Across the Mendip Hills and within Cheddar Gorge itself, herds of cattle, goats and soay sheep graze the land, keeping scrub in check and creating open, sunlit areas where insects thrive. These grazed pastures are especially valuable to greater horseshoe bats, who rely on dung beetles and other invertebrates linked to traditional livestock farming. It’s a perfect example of how agriculture, wildlife, and landscape can work hand in hand.

Our monitoring work, carried out annually since 2017, helps us keep track of how the bat populations are doing, detect any changes early, and guide decisions that support their future. It’s a reminder that Cheddar Gorge isn’t just a geological wonder—it’s home for some of the UK's most iconic and vulnerable wildlife."